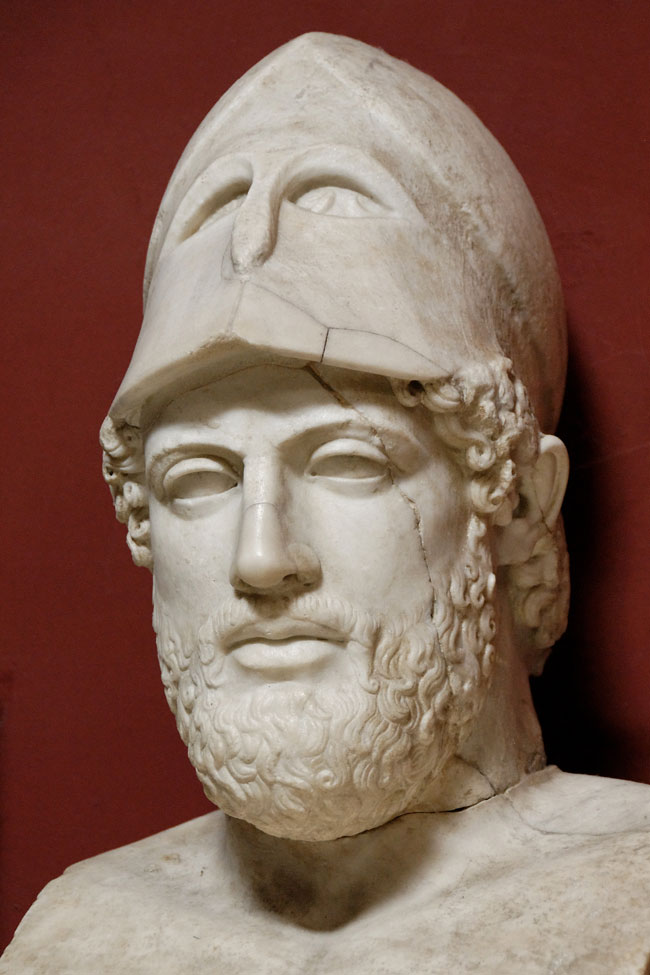

“Make up your minds that happiness depends on being free, and freedom depends on being courageous.”

That’s Pericles, speaking to the public at a ceremonial burial of Athenian soldiers 2,445 years ago.

Now, we only have the words—we don’t know what Pericles’s delivery of them was like, but we do know that his performance was stirring enough to prompt the historian Thucydides to record the speech in his History of the Peloponnesian War, and the words on their own are meaningful enough that we read them with admiration to this day.

What is it that makes good speeches so timeless and memorable? How has this art form remained so consistently compelling, for so long? Why do we love to listen?

Humans have been able to communicate through spoken language for tens of thousands of years, and very early on developed an oral tradition of passing down histories and cultural traditions.

Even as they developed writing systems, the big ancient civilizations—the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians, the Chinese—continued to give regard to eloquent and wise speakers.

It wasn’t until the rise of the Ancient Greek city states, though, that anyone decided to look at why good speakers were so good, and how their skills could emulated and learned.

That’s where things really start: in Pericles’s Athens—2,500 or so years ago. The new democracy, with its emphasis on freedom of choice and the people’s will, relied on the ability of every vote-wielding man (always a man at that time) to persuade his peers to support one position or another.

Public speaking of the persuasive variety—rhetoric—was the basis of decision-making, with a focus on strong logic and good reason. The skill to speak persuasively decided who held power, so schooling in the subject was in high demand.

Though traveling teachers known as the sophists taught gave popular lectures on speaking, it was Aristotle, in On Rhetoric, who set out the bedrock teachings—ideas that remain hugely influential dozens of centuries later.

To learn to do something effectively, you need to know what makes it effective—why it works.

In his treatise, Aristotle outlined the modes of persuasion: ethos (make a case for your authority as a speaker), pathos (make an appeal to the audience’s emotions), and logos (make an appeal to the audience’s logic). This was the first real analysis of how to speak effectively—how to make audiences want to listen.

Twenty-five hundred years later, I’m helping my speakers finish the work that Pericles and Aristotle started. Next time, I’ll take a look at Classical Romans who came up with a system to constantly produce and present effective speeches.

Add comment